Memento mori (and the science of death awareness)

Every morning I wake to a reminder of my delicate mortality.

Every morning, I wake to a reminder of my delicate mortality.

🌅 My view from bed every morning

Close up of Memento Mori poster

The framed poster is a symbol of the inevitability of death. Memento mori is Latin for “remember you have to die.” I discovered this concept after falling down a rabbit hole searching out contemporary information on the ancient philosophy of Stoicism and found The Daily Stoic, a website run by author Ryan Holiday, selling various prints and medallions imprinted with stoic reflections such as memento mori. Eventually, I found StoicReflections that offered the “life calendar” print shown above.

“It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste much of it. Life is long enough, and it has been given in sufficiently generous measure to allow the accomplishment of the very greatest things if the whole of it is well invested.”

The average lifespan is 80 years or 4160 weeks. Glancing up at the poster allows me to see my life in weekly blocks and how many “empty” blocks I have left. Every weekend I grab my Sharpie and fill in another box.

It may sound morbid or depressing, but the weekly ritual of filling in a new square grounds me in the present and motivates me to make the most of each day. I don’t necessarily mean working harder or stressing over some legacy to leave behind either. The persistent reminder elevates me with gratitude to appreciate simple, joyful moments, pushes me to enhance my physical health, and reprioritize meaningful goals. I reflect on how I will make my week count.

No one sees the impact of death on the living more than a funeral director. In her 2014 memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, Caitlin Doughty says: “Death is the engine that keeps us running, giving us the motivation to achieve, learn, love, and create.”

Many others, though, tend to avoid the topic and will even deny its reality even in the face of a terminal diagnosis. I wondered why and questioned if scientists had attempted to analyze the effects of death awareness on human behaviour.

In early studies, psychologists focused on the negative impacts of death awareness, called terror management theory, or TMT. Most TMT studies examined how existential fear promoted aggression, greed, materialism, and rejection of those with different beliefs and values. The theory also proposes we have psychological systems in place to minimize anxiety caused by death awareness. Researchers concluded that we cling to religious beliefs (such as heaven or the afterlife) or symbolic cultural milestones (having children, writing a book 😀) to transcend death (Vail et al.).

Or we unconsciously try to avoid the possibility of our mortality altogether.

In 2019, researchers watched the brain activity of volunteers when presented with either neutral stimuli or those associated with death (such as the words “burial” and “funeral”). Researchers projected the phrases alongside images of themselves or strangers. They found that when they flashed up a person’s own face next to “death-related” words, their brain dampened activity in specific areas. In other words, the subject’s brain tended to suppress any link of death to themselves (Dor-Ziderman et al.).

Brain activity differences when comparing “control images with Self “ > “death images with Self.” Colour signal shows brain regions with significant differences. Authors concluded that dampened brain activity with “death images with self” leads to decreased sensing of death awareness.

The lead researcher on the study, Dr. Avi Goldstein, said: "This suggests that we shield ourselves from existential threats, or consciously thinking about the idea that we are going to die, by shutting down predictions about the self, or categorizing the information as being about other people rather than ourselves” (Doubting death: how our brains shield us from mortal truth, The Guardian).

Scientists later turned their attention to the positive aspects of death awareness. They found that “management of death concerns can play a key role in motivating people to stay true to their virtues, to build loving relationships, and to grow in fulfilling ways” (Vail et al.).

In her personal development/awareness seminars, my mother repeatedly said, “Perspective - use it or lose it.” When it comes to viewing our mortality, we can choose our perspective: a threat or an opportunity. I prefer the latter. Reminding myself of my mortality refocuses me and prompts me to take action and seek out things that make me happier to enjoy each day. Days of the week can just slip by if we don’t pay attention, and the last thing I wanted was to have my 9-5 career as my sole metric of accomplishment. I want to see, feel and experience more.

How can we slow down and make each day count? Here are some hints for bringing you closer to living the life you want, making sure your day never feels wasted:

🚏 Change your routine. We often get set in our way and go about our days on autopilot. We walk the same routes to work. We visit the same coffee shops. We bike or run on familiar streets. Instead, take the road less travelled and take a different path to work. Go for a run in the other direction and buy that coffee at a newly discovered shop. Unplug your earphones and listen to the birds instead. Leave your phone on the charger — you will see and experience newness, and your days will expand.

Awareness of your mortality may even motivate a lifestyle change, an opportunity to adopt new habits such as eating quality foods and moving more.

📓 Create a memory journal. Reflect on your day, and write a couple of sentences about something that happened that day. Jot down any insights that sparked in your mind. During the pandemic, our days can feel repetitive and unexciting, but memories surface all the time — and that can be your entry for the day.

In his book Storyworthy, Matthew Dicks writes, “I decided that at the end of every day, I’d reflect upon my day and ask myself one simple question — if I had to tell a story from today, what would it be? As benign and boring and inconsequential as it might seem, what was the most storyworthy moment from my day?”

I record my storyworthy moments in a “5-year memory book.” The best journal I found is the Leuchtturm1917 brand.

Each page is dated and divided into five sections that correspond to that day of each year. As the years roll past, you can read what you wrote last year, or two years ago, and so on. Some of the other 5-year memory books are narrow and offer limited space for each entry. The Leuchtturm1917 brand leaves room for at least 5-6 lines.

💡 Indulge your curiosity. It might be as simple as taking a cooking class, playing around with watercolours or reading a different book genre. For me, it involves expressions of creativity. While writing my first book, I experienced explosive moments of joy — a rush of feeling alive. Recently, I began working on a novel. The move from nonfiction was scary, but I allowed my curiosity to push through the fear. Soon my imagination took over, and ideas spilled onto the page, and that thrill of creation burned within. It didn’t matter if the book was ever published — the story was for me, and I felt imbued with a sense of accomplishment and contentment. Today mattered.

My daily mortality reminder and all of my suggestions above are all different facets of mindfulness. If I were to add a fourth tip, it would be to meditate, even for ten minutes a day, using the Calm, Headspace or Waking Up apps on your phone. Slowing down and paying attention makes our days feel full and allows us to add more creativity, experiences, and joy to each day.

The average lifespan may be 4160 weeks, but in reality we don’t know how much time we have left. Accidents can happen anytime. My research on brain tumours and cancer biology has made me appreciate the fragility of life. I aim to make each of my remaining days and weeks count.

How will you spend your week?

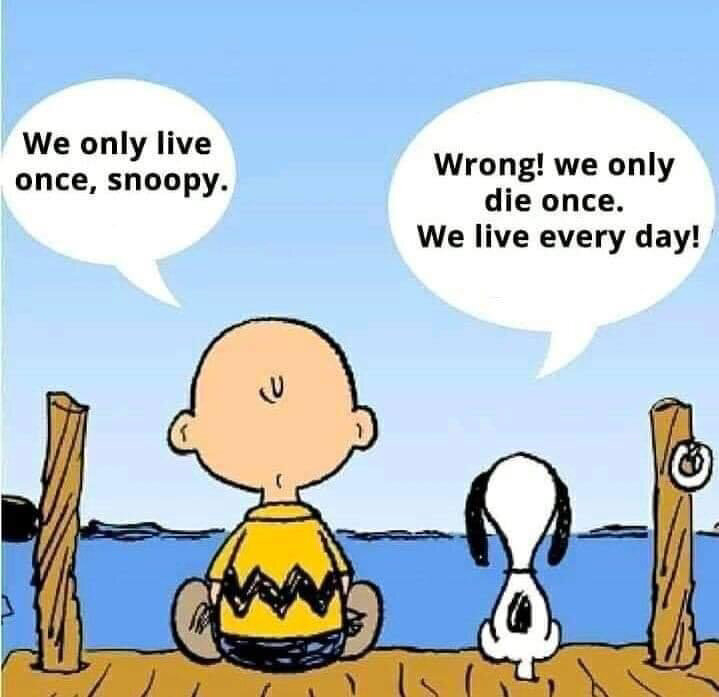

credit: The Peanuts by Charles Schulz

A Deciduous Friendship (and the science of how leaves change their colour)

On a walk through the park I realized I couldn’t remember what caused leaves to change their colour in the fall. Little did I realize that the science of leaf colour would give me insight into a friendship.

Hands down, autumn is my favourite season of the year. Although a harbinger of winter, fall is the time of cosy throw covers, warm fireplaces and the anticipation of holiday celebrations. As the last days of October transition into November, Toronto has a chill in the air, darkening early evenings, and spectacular landscapes painted with hues of orange, yellow and red.

On an early morning walk with Madeline (also known as #Writer’sBlock), I noticed that the trees had hit their peak in colour change, and many were dramatically shedding their colourful bounty, decorating the ground below. Marvelling at the colours, I realized how little I knew about why leaves change their colour.

I’m sure I must have learned it at some point during a university botany class, but as Madeline and I walked through the park, the details escaped me. I guessed it was the temperature change. Cold weather killing off the leaves made sense.

As I dug deeper into the science of autumn leaf transformation, I learned temperature was only part of the story. Surprisingly, my search for answers would also lead to an insight into a friendship that was troubling me.

There are two main types of trees: deciduous and coniferous. Deciduous trees have leaves that fall off yearly, while coniferous trees, such as the evergreens, have needles or scales that remain intact year-round.

I’d assumed the leaves changed colour as the temperature dropped when, in fact, it’s the gradual decrease in daylight that triggers molecular changes within the cells of the tree leaves. To survive, the tree uses photosynthesis to generate energy by harnessing sunlight to convert carbon dioxide in the air into a usable power source — sugars. In mammals, the power generators of the cell are mitochondria, while plants rely on spheroid structures called chloroplasts. If you were to put a plant leaf under the microscope, you would see thousands of oblong green discs embedded within each plant cell. The abundant chloroplasts are what gives the leaf its green colour, masking the true colour of the tree’s foliage.

Microscopic view of plant cells. Green = chloroplasts. Note hints of red in each cell, in fall this leaf likely turns red.

As the amount of sunlight decreases in the fall, the process of photosynthesis begins to fade, just like the leaves. Each year the leaves don’t actually change colour. Instead, the sunlight-reliant green colour from chloroplasts fades to reveal each deciduous tree’s unique natural pigments. The dazzling hues of yellow, orange and red were always there, the robust green colour of chlorophyll just overshadowed them.

As autumn approaches, without enough sunlight, the deciduous tree can no longer create the energy it needs to survive if it were to carry on, business as usual. Suddenly, the thousands of fading leaves on the tree’s branches are a massive energy liability.

Instead, to conserve and store energy to survive the winter months, the tree closes off the connection to the leaves in a process called abscission. A good gust of wind and the leaf spirals away into the breeze.

As I considered the tree’s struggle to conserve its energy by severing the connection to its leaves, I thought of a friendship that left me struggling. Over the years, the differences between my friend Joseph and I began to overshadow what we had in common. I’d gotten far too comfortable with his constant negativity, but when he returned to lying and deceitful behaviour, I made my decision. I didn't have the energy to keep Joseph in my life. Like the deciduous tree that cuts off the connection to its leaves in the dwindling autumn sunlight, I too needed to sever my connection to Joseph to save my own energy balance. For my mental well-being, I also needed to try a little abscission.

In shedding my friendship with Joseph, I realized I was no longer prepared to settle for a deciduous friendship.

I want evergreen friendships.

credits: Three trees: ©mirifadapt (via Adobe Stock); chloroplasts: ©tonaquatic (via Adobe Stock); diagram: generated using assets from ©sudowoodo and ©bokasana (via Adobe Stock); evergreens: ©Ioan Panaite (via Adobe Stock).